Whether you're diabetic or not, it is important that you

keep your immune system strong to protect you against most diseases and

illness, including the flu and the common cold.

Your immune system protects your body against disease by

identifying and killing pathogens and tumor cells. It detects a wide variety of

agents, from viruses to parasitic worms, and needs to distinguish them from

your own healthy cells and tissues in order to function properly. Detection is

complicated as pathogens can evolve rapidly, and adapt to avoid the immune

system and allow the pathogens to successfully infect our bodies.

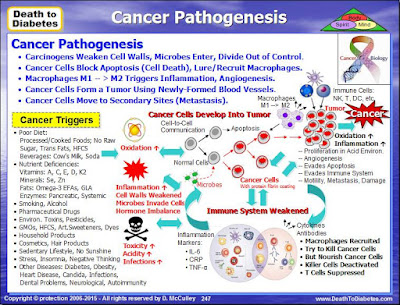

When you catch a cold or the flu; or, when you develop a

disease such as diabetes or cancer, the primary reason is due to inflammation and a weakened immune system that is unable to defend your body against

the invading pathogens, viruses, fungi, and parasites; and the other health issues

such as insulin resistance, high blood pressure, nutrient deficiencies, poor

diet, and toxins.

Consequently, two of the most critical steps in being

able to successfully prevent or defeat

any illness or disease are to reduce the inflammation

and strengthen the immune system. But, first,

let's take a look at how the immune system works.

Immune System: 3 Lines of Defense

The

immune system is a collection of special cells, tissues and molecules that

protects the body from numerous pathogenic microbes and toxins, utilizing 3

lines of defense:

1.

Physical and Chemical Barriers (Innate Immunity)

2.

Nonspecific Resistance (Innate Immunity)

3.

Specific Resistance (Acquired or Adaptive Immunity)

1st Line

of Defense: Physical and Chemical Barriers

Physical

Barriers include: the skin; mucous membranes; hair within the nose; cilia which

lines the upper respiratory tract; urine which flushes microbes out of the

urethra; defecation and vomiting which expel microorganisms.

Chemical

Barriers include: lysozyme, an enzyme produced in tears, perspiration, and

saliva can break down cell walls and thus acts as an antibiotic (kills

bacteria); stomach gastric juice which destroys bacteria and most toxins; sebum

(unsaturated fatty acids) provides a protective film on the skin and inhibits

growth.

2nd Line

of Defense: Nonspecific Resistance (Innate Immunity)

The

second line of defense is nonspecific resistance that destroys invaders in a

generalized way without targeting specific individuals. White blood cells

(called phagocytes) ingest and destroy all microbes that pass into body

tissues.

In

addition, there is an inflammatory response in the localized tissue where the

pathogen invaded the body or where the tissue was damaged due to a cut or

wound. Inflammation brings more white blood cells to the site where the

microbes have invaded. The inflammatory response produces swelling, redness,

heat, pain and fever. Fever inhibits bacterial growth and increases the rate of

tissue repair during an infection.

3rd Line

of Defense: Specific Resistance (Acquired Immunity)

The third line of defense is specific resistance. This

system relies on antibodies, which are produced by specific immune cells

(called B cells) in response to the antigens on the surface of the invading

pathogens.

When an antigen is detected by a macrophage, this causes

the T cells to become activated. The activation of T cells by a specific

antigen is called cell-mediated immunity. The body contains millions of

different T cells, each able to respond to one specific antigen.

The T cells secrete interleukin 2, which causes the

proliferation of certain cytotoxic T cells and B cells. T cells stimulate B

cells to divide, forming plasma cells that are able to produce antibodies and

memory B cells.

If the same antigen enters the body later, the memory B

cells divide to make more plasma cells and memory cells that can protect

against future attacks by the same antigen.

When the T cells activate (stimulate) the B cells to

divide into plasma cells, this is called antibody-mediated immunity.

Antibodies (also called immunoglobulins) are Y-shaped

proteins that circulate through the blood stream and bind to specific antigens,

thereby attacking microbes. The antibodies are transported through the blood

and the lymph to the pathogen invasion site.

The body contains millions of different B cells, each

able to respond to one specific antigen.

Antibodies bind to an antigen, preventing its normal

function or making it easier for phagocytic cells to ingest them; or, they

activate a complement protein that kills the pathogen or signals other white

blood cells; or they binds to the surface of macrophages to further facilitate

phagocytosis.

Immune System Components

The major components of the immune system include the

following:

Thymus: is located between your

breast bone and your heart and is responsible for producing thymosin, which

helps to activate T cells. As we get

older, this organ shrinks over 80% and produces less thymosin and may be one of the reasons why

our immune system weakens and we become more susceptible to certain diseases.

Spleen: filters the blood

looking for foreign cells (the spleen is also looking for old red blood cells

in need of replacement). A person missing their spleen gets sick much more

often than someone with a spleen.

Lymph system: includes the tissues

and organs, including the bone marrow, spleen, thymus, and lymph nodes, that

produce and store cells that fight infection and disease. The channels that

carry lymph are also part of this system.

Lymph is a clear-like liquid that bathes the cells with

water and nutrients. Lymph is blood plasma -- the liquid that makes up blood

minus the red and white cells. Think about it -- each cell does not have its

own private blood vessel feeding it, yet it has to get food, water, and oxygen

to survive. Blood transfers these materials to the lymph through the capillary

walls, and lymph carries it to the cells.

The cells also produce proteins and waste products and

the lymph absorbs these products and carries them away. Any random bacteria

that enter the body also find their way into this inter-cell fluid. One job of

the lymph system is to drain and filter these fluids to detect and remove the

bacteria. Small lymph vessels collect the liquid and move it toward larger

vessels so that the fluid finally arrives at the lymph nodes for processing.

Bone marrow: produces new blood

cells, both red and white including B cells. In the case of red blood cells the

cells are fully formed in the marrow and then enter the bloodstream. In the

case of some white blood cells, the cells mature elsewhere. The marrow produces

all blood cells from stem cells. They are called "stem cells" because

they can branch off and become many different types of cells - they are

precursors to different cell types. Stem cells change into actual, specific

types of white blood cells.

White blood cells: also called leukocytes,

are probably the most important part of your immune system. These cells work

together to destroy bacteria and viruses. The different types of white blood

cells include: Neutrophils, Eosinophils, Basophils, Monocytes, Lymphocytes, B cells,

T cells, Helper T cells, Suppressor T cells, Killer T cells, Granulocytes,

Plasma cells, Phagocytes, Dendritic cells, Natural Killer cells, and

Macrophages.

Antibodies: (also referred to as

immunoglobulins) are produced by white blood B cells. They are Y-shaped

proteins that each respond to a specific antigen

(bacteria, virus or toxin). Antibodies come in five classes: Immunoglobulin A (IgE),

Immunoglobulin D (IgE), Immunoglobulin E (IgE), Immunoglobulin G (IgG), and Immunoglobulin

M (IBM).

Antigen: The surface of every

cell is covered with molecules that give it a unique set of characteristics.

These molecules are called antigens. Antigens are generally fragments of

protein or carbohydrate molecules. There are millions of different antigens and

each one has a unique shape that can be recognized by white blood cells. The

white blood cells then produce antibodies to match the shape of the antigens.

Some antigens (e.g. associated with bacteria, viruses,

pollen, etc.) stimulate an immune response by a white blood (B) cell to

generate antibodies specific to that antigen that matches the shape of the

antigen.

Now the antibody can bind to that specific antigen to

make it easier for other white blood cells to engulf or attack the bacteria or

virus who brings the antigen with them.

The antigens on the surface of bacteria, viruses and

other pathogenic cells are different from those on the surface of your own

cells. This enables your immune system to distinguish pathogens from cells that

are part of your body. Antigens are also found in foods like peanuts and on the

surface of foreign materials like pollen, pet hairs and house dust where they

can be responsible for triggering an allergy, hay-fever or asthma attacks.

Lymphokines: are several hormones

generated by components of the immune system. It is also known that certain

hormones in the body suppress the immune system. Steroids and corticosteroids

(components of adrenaline) suppress the immune system.

Tymosin (thought to be produced

by the thymus) is a hormone that encourages lymphocyte production.

Interleukins are another type of hormone

generated by white blood cells. For example, Interleukin-1 is produced by

macrophages after they eat a foreign cell. IL-1 has an interesting side-effect

- when it reaches the hypothalamus it produces fever and fatigue. The raised

temperature of a fever is known to kill some bacteria.

Lymphokines are a subset of cytokines that are produced

by lymphocytes. They are protein mediators typically produced by T cells to

direct the immune system response by signaling between its cells.

Lymphokines

have many roles, including the attraction of other immune cells, including

macrophages and other lymphocytes, to an infected site and their subsequent

activation to prepare them to mount an immune response. Circulating lymphocytes

can detect a very small concentration of lymphokine and then move up the

concentration gradient towards where the immune response is required.

Lymphokines aid B cells to produce antibodies.

Important lymphokines secreted by the T helper cell

include: interleukin 2, 3, 4, 5, 6; granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating

factor; and interferon-gamma.

Cytokines: are small peptides

that act as signaling systems within the body. Because they facilitate

communication between the innate and adaptive immune systems, cytokines are a

key factor in fighting infection and maintaining homeostasis.

Cytokines include chemokines, interferons, interleukins,

lymphokines, tumor necrosis factor. Cytokines are produced by a broad range of

cells, including immune cells like macrophages, B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes

and mast cells, as well as endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and various stromal

cells.

Proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 1 (IL-1)

and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) are released defensively in

response to infection and trauma. Anti-inflammatory cytokines such as

transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) and IL-10 oppose the action of the

proinflammatory cytokines and promote healing.

Some cytokines are chemical switches that turn certain

immune cell types on and off. One cytokine, interleukin 2 (IL-2), triggers the

immune system to produce T cells. IL-2’s immunity-boosting properties have

traditionally made it a promising treatment for several illnesses.

Elevated plasma levels of proinflammatory cytokines are

biomarkers of inflammation and/or disease. An imbalance between the activity of

proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines is believed to affect disease

onset, course, and duration.

Anti-inflammatory cytokines is a general term for those

immunoregulatory cytokines that counteract various aspects of inflammation, for

example cell activation or the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and

thus contribute to the control of the magnitude of the inflammatory responses.

These mediators act mainly by the inhibition of the production of

pro-inflammatory cytokines.

The major

anti-inflammatory cytokines are IL4, IL10, and IL13, and IL35. Other

anti-inflammatory mediators include IL16, IFN-alpha, TGF-beta, IL1ra, G-CSF, as

well as soluble receptors for TNF or IL6.

Tonsils: are lymphoepithelial

tissues facing into the aerodigestive tract. These tissues are the immune

system's first line of defense against ingested or inhaled foreign pathogens.

The fundamental immunological roles of tonsils aren't yet understood.

Lymph nodes are distributed widely

throughout areas of the body, including the armpit and stomach, and linked by

lymphatic vessels. Lymph nodes are garrisons of B, T and other immune cells.

Lymph nodes act as filters or traps for foreign particles and are important in

the proper functioning of the immune system. They are packed tightly with the

white blood cells, called lymphocytes and macrophages.

Skin: is one of the most

important parts of the body because it interfaces with the environment, and is

the first line of defense from external factors, acting as an anatomical

barrier from pathogens and damage between the internal and external environment

in bodily defense. Langerhans cells in the skin are part of the adaptive immune

system.

Liver: has a wide range of

functions, including immunological effects—the reticuloendothelial system of

the liver contains many immunologically active cells, acting as a

"sieve" for antigens carried to it via the portal system.

They also store information on these non-self substances

to be able to react faster the next time. The large bowel also contains

bacteria that belong to the body, called gut flora. These good bacteria in the

large bowel make it difficult for other pathogens to settle and to enter the

body.

Innate and Adaptive Immunity

The protection provided by the immune system is divided

into two types of reactions: reactions of innate immunity and reactions of

adaptive or acquired immunity.

The innate immune

system consists of cells and proteins that are always present and ready to

mobilize and fight microbes at the site of infection. The main components of

the innate immune system are 1) physical epithelial barriers; 2) phagocytic

leukocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils); 3) monocytes (which develop

into macrophages); 4) dendritic cells; 5) a special type of lymphocyte called

natural killer (NK) cells; and, 6) circulating plasma proteins. Other

participants in innate immunity include the complement system and cytokines

such as interleukin 2 (IL-2).

Innate immune cells express genetically encoded

receptors, called Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which recognize general danger-

or pathogen-associated patterns. Collectively, these receptors can broadly

recognize viruses, bacteria, fungi, and even non-infectious problems. However,

they cannot distinguish between specific strains of bacteria or viruses.

There are numerous types of innate immune cells with

specialized functions. They include neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, mast

cells, monocytes, dendritic cells, and macrophages.

Their main feature is the ability to respond quickly and

broadly when a problem arises, typically leading to inflammation. Innate immune

cells also are important for activating adaptive immunity. Innate cells are

critical for host defense, and disorders in innate cell function may cause

chronic susceptibility to infection.

The adaptive (or

acquired) immune system is called into action against pathogens that are

able to evade or overcome innate immune defenses. Components of the adaptive

immune system are normally silent; however, when activated, these components

“adapt” to the presence of infectious agents by activating, proliferating, and

creating potent mechanisms for neutralizing or eliminating the microbes. There

are two types of adaptive immune responses: 1) humoral

immunity, mediated by antibodies produced by B lymphocytes; and, 2) cell-mediated immunity, mediated by T lymphocytes.

The adaptive immune response is more complex than the

innate. The antigen first must be processed and recognized. Once an antigen has

been recognized, the adaptive immune system creates an army of immune cells

specifically designed to attack that antigen. Adaptive immunity also includes a

"memory" that makes future responses against a specific antigen more

efficient.

Each receptor recognizes an antigen, which is simply any molecule that may bind to a BCR or TCR. Antigens are derived from a variety of sources including pathogens, host cells, and allergens. Antigens are typically processed by innate immune cells and presented to adaptive cells in the lymph nodes.

If a B or T cell has a receptor that recognizes an antigen from a pathogen and also receives cues from innate cells that something is wrong, the B or T cell will activate, divide, and disperse to address the problem. B cells make antibodies, which neutralize pathogens, rendering them harmless. T cells carry out multiple functions, including killing infected cells and activating or recruiting other immune cells.

Certain T cells (Helper T) help activate B cells to secrete antibodies and macrophages to destroy ingested microbes. They also help activate other T cells called cytotoxic T cells to kill infected target cells. As dramatically demonstrated in AIDS patients, without Helper T cells we cannot defend ourselves even against many microbes that are normally harmless.

However, Helper T cells themselves can only function when activated to become effector cells. They are activated on the surface of antigen-presenting cells (APC), which mature during the innate immune responses triggered by an infection.

The

innate responses also dictate what kind of effector cell a Helper T cell will

develop into and thereby determine the nature of the adaptive immune response

elicited.

The

adaptive immune response has a system of checks and balances to prevent

unnecessary activation that could cause damage to the host. If a B or T cell is

auto-reactive, meaning its receptor recognizes antigens from the body's own

cells, the cell will be deleted. Also, if a B or T cell does not receive

signals from innate cells, it will not be optimally activated.

Immune

memory is a feature of the adaptive immune response. After B or T cells are activated,

they expand rapidly. As the problem resolves, cells stop dividing and are

retained in the body as memory cells. The next time this same pathogen enters

the body, a memory cell is already poised to react and can clear away the

pathogen before it establishes itself.

A

further aspect of the adaptive immune system worth mentioning is its role in

monitoring body cells to check that they aren't infected by viruses or

bacteria, for instance, or in order to make sure that they haven't become

cancerous. Cancer occurs when certain body cells 'go wrong' and start dividing

in an uncontrolled way.

The Major Cells of the Immune System

The key tissues and organs involved with the immune

system include the lymph nodes, spleen, tonsils, bone marrow, thymus, and lymphatic

tissue. The key immune cells are white blood cells (or leukocytes). The (3)

major categories of white blood cells are: granulocytes,

lymphocytes and monocytes.

Granulocytes are characterized by the presence of granules in

their cytoplasm which contain digestive enzymes that kill various types of

bacteria and parasites. Granulocytes are also called polymorphonuclear

leukocytes (PMN, PML, or PMNL) because of the varying shapes of the nucleus,

which is usually lobed into three segments. The principal types of granulocytes

are neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, and mast cells.

Lymphocytes come in three major types:

B-lymphocytes (or

B cells), T-lymphocytes(or T cells) and natural killer (NK) cells.

Lymphocytes start out in the bone marrow and either stay

there and mature into B cells, or they leave for the thymus gland, where they

mature into T cells.

B cells produce antibodies in

the humoral immune response and are like the body's military intelligence

system, seeking out their targets and sending defenses to lock onto them. With

the help of T cells, B cells make special Y-shaped protein antibodies, which stick

to antigens on the surface of bacteria, stopping them in their tracks, creating

clumps that alert your body to the presence of intruders.

Plasma cells, also called plasma B

cells, secrete large volumes of antibodies.

Memory B cells are important in

generating an accelerated and more robust antibody-mediated immune response in

the case of re-infection (also known as a secondary immune response).

Regulatory B

cells (Bregs) participates in immunomodulations and in suppression of immune

responses. via production of anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin 10 (IL-10).

T cells recognize and kill

virus-infected cells directly. Some help B cells to make antibodies, which

circulate and bind to antigens. Others send chemical instructions (cytokines)

to the rest of the immune system. Types of T cells include Helper T (Th),

Memory T (Tm), Cytotoxic T (Tc), Suppressor T (Treg), and Effector T cells.

Helper T Cells

(Th) help

activate B cells to secrete antibodies and macrophages to destroy ingested

microbes, but they also help activate cytotoxic T cells to kill infected target

cells. Note: In AIDS patients,

without helper T cells we cannot defend ourselves even against many microbes

that are normally harmless.

Memory T Cells

(Tm) are

derived from normal T cells that have learned how to overcome an invader by

‘remembering’ the strategy used to defeat previous infections. At a second

encounter with the invader, memory T cells can reproduce to mount a faster and

stronger immune response than the first time the immune system responded to the

invader.

Cytotoxic T

Cells (Tc)

are lymphocytes that kill invading pathogens including cancer cells, cells that

are infected (particularly with viruses), or cells that are damaged in other

ways. Tc cells kill their targets by programming them to undergo apoptosis. The

elimination of infected cells without the destruction of healthy tissue

requires the cytotoxic mechanisms of CD8 T cells to be both powerful and

accurately targeted.

Suppressor T

Cells (Treg)

suppress the immune response after invading organisms are destroyed by releasing

their own lymphokines to signal all other immune-system participants to cease

their attack.

Effector T

cells

(also called Helper T (Th) cells), are the functional cells for executing

immune functions. Balanced immune responses can only be achieved by proper regulation

of the differentiation and function of Th cells.

Natural killer

(NK)

cells are cytotoxic cells that participate in the innate immune response and

attack in packs by releasing substances that perforate the "skin" of

their victims -- this is death by cell lysis.

Monocytes, which are the largest

of all leukocytes, fight off bacteria, viruses and fungi. Originally formed in

the bone marrow, they are released into the blood and tissues. When certain

germs enter the body, they quickly rush to the site for attack within 8–12

hours.

Monocytes have several functions to help you ward off

diseases and infections. To help you remember what they do, note that each

function begins with the letter 'M': Munch, Mount and Mend.

Munch: Monocytes have the

ability to change into another cell form called macrophages before facing the germs.

In response to inflammation signals, monocytes move quickly to sites of

infection in the tissues and divide/differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells to elicit an immune

response. They change into macrophages when they move from the bloodstream to

the tissues.

They consume, or munch, on harmful bacteria, fungi and

viruses. Then, enzymes in the monocyte kill and break down the germs into

pieces.

Mount: Monocytes help other

white blood cells identify the type of germs that have invaded the body. After

consuming the germs, the monocytes take parts of those germs, called antigens,

and mount them outside their body like flags. Other white blood cells see the

antigens and make antibodies designed to kill those specific types of germs.

Mend: Monocytes help mend

damaged tissue by stopping the inflammation process. They remove dead cells

from the sites of infection, which repairs wounds. They have also shown to

influence the formation of some organs, like the heart and brain, by helping

the components that hold tissues together.

Macrophages are derived from

monocytes, granulocyte stem cells, or the cell division of pre-existing

macrophages. Macrophages do not have granules but have receptors to detect,

capture and ingest pathogens. Macrophages are found throughout the body in

almost all tissues and organs, just below the surface of the skin and mucous

membranes — any place where a pathogen could get through the first line of

defense. Macrophages cause inflammation through the production of

interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and TNF-alpha. Macrophages are usually only found

in tissue and are rarely seen in blood circulation.

They take up and destroy necrotic cell debris and foreign

material including viruses, bacteria, and tattoo ink. In wound healing,

macrophages take on the role of wound protector by fighting infection and

overseeing the repair process. Macrophages also produce chemical messengers,

called growth factors, which help repair the wound.

When inflammation occurs, monocytes undergo a series of

changes to become macrophages and target cells that need eliminating.

Once engulfed, cellular enzymes inside the macrophage

destroy the ingested particle. Some macrophages act as scavengers, removing

dead cells while others engulf microbes.

Another function of macrophages is to alert the immune

system to microbial invasion. After ingesting a microbe, a macrophage presents

a protein on its cell surface called an antigen, which signals the presence of

the antigen to a corresponding T helper cell.

Macrophages change into foam

cells in the blood vessel walls (endothelium), where they try to

fight atherosclerosis by engulfing excessive cholesterol engulf large amounts

of fatty substances, usually cholesterol. Foam cells are created when the body

sends macrophages to the site of a fatty deposit on the blood vessel walls. The

macrophage wraps around the fatty material in an attempt to destroy it and

becomes filled with lipids (fats). The lipids engulfed by the macrophage give

it a "foamy" appearance.

Foam cells are often found in the fatty streaks and

plaques inside the blood vessel walls. Foam cells do not give off any specific

signs or symptoms, but they are part of the cause of atherosclerosis. Foam cell

development can be slowed, however. Decreasing low density lipoprotein (LDL)

cholesterol and increasing high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol will

remove the lipids that the macrophages engulf to become foam cells.

In addition to the monocytes and macrophages, the other types of white

blood cells include neutrophils, basophils, eosinophils, mast cells

and dendritic cells.

Neutrophils defend against bacterial or fungal infection and other

very small inflammatory processes. They are usually the first responders to

microbial infection; their activity and death in large numbers forms pus.

Basophils are chiefly responsible for allergic reactions and

antigen response by releasing the chemical histamine, which helps to trigger

inflammation, and heparin, which prevents blood from clotting.

Eosinophils primarily deal with

parasitic worm infections. They are also the predominant inflammatory cells in

allergic reactions.

Mast cell is a type of granular

basophil cell in connective tissue that releases heparin, histamine, and

serotonin during inflammation and allergic reactions.

Dendritic

cells

(DCs), which can also develop from monocytes, are an important

antigen-presenting cell (APC) whose main function is to process antigen

material and present it on the cell surface to the T cells in order to activate

the T cells. They act as messengers between the innate and the adaptive immune

systems. Once activated, dendritic cells migrate to the lymph nodes where they

interact with T cells and B cells to initiate and shape the adaptive immune

response.

Note: Antigens are molecules

from pathogens, host cells, and allergens that may be recognized by adaptive

immune cells.

Antigen-presenting

cells

(APCs) like DCs are responsible for processing large molecules into

"readable" fragments (antigens) recognized by adaptive B or T cells

in order to activate them. However, antigens alone cannot activate T cells.

They must be presented with the appropriate major histocompatibility

complex (MHC) molecule "tags" expressed on the APC. MHC

provides a checkpoint and helps immune cells distinguish between self and non-self

cells.

An APC can be any of various cells (as a macrophage or a

B cell) that take up and process an antigen into a form that when displayed at

the cell surface in combination with an MHC molecule is recognized by and

serves to activate a specific helper T cell using their T-cell receptors (TCRs).